The kibbutz near Haifa, 1945*

„The truck will be coming for you tomorrow after breakfast,“ we were told. „You are going to a Kibbutz.“ I had no idea where or what a „kibbutz“ was, but I asked no questions, neither did Peter. We had nowhere else to go. All we had to do was be there when they called out our names and get on the truck.

It was a delivery truck covered by a pink tarpaulin. We settled in the back corners, watching the scenery pull away, rolling along with the morning traffic. Sometime later, the truck slowed down, turned off the main road, and after short bumpy ride, it stopped. A few one-story gray wooden buildings, unconnected by road or sidewalk and perched on blocks of stone, were scattered in the dunes, like a train derailed in a desert. Tall grass was growing in patches around, between and under the buildings. In the distance, under a bright sun, a group of children were standing still, looking at us.

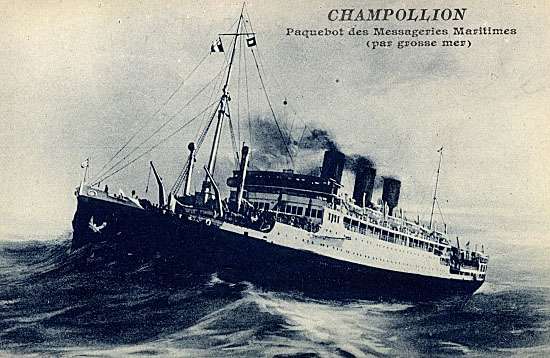

The driver brought us to the wrong place was my first thought. It must be a mistake; this couldn’t possibly be the place where only the luckiest of people get to go to. The place they told me about at the transit camp in Marseilles where you will be free, never have to fear, or worry about a thing: „It is our paradise!“ I repeated it to myself over and over, sitting on the truck, looking out at the scene of desolation ringed by barbed-wire.

In broken German and a polite smile, the driver urged us to get off his truck. I ignored him, pretending not to understand, and retreated into my corner. Seeing that we were not getting off, the children came over. After they exchanged a few words with our driver, he dropped the smile and became insistent, stamping his feet in the sand and flailing his arms in the air, ordering us to get off. When that failed, he charged the truck and climbed on with a groan. At which point, Peter and I jumped off.

We followed the children to an isolated stone building near the barbed-wire fence: the children’s house. Waiting for us at the door, in a white apron, was the metapelet. [The person on the kibbutz, usually a woman, who took care of the children when they were not in the classroom.] She showed us to the shower room and in perfect German ordered us to undress. Surprised, I stared at her, making no move toward undressing. Neither did Peter. After a few minutes of silence, she went in to a long lecture about having to clean us up before lunch and having no time to play games. Though she was good-natured about it, my impression was that there was no getting past her. I undressed.

She brought out a pair of scissors and unceremoniously began cutting my hair. While it was sliding down my face, I could see Peter’s emaciated legs, his hands folded over his privates, waiting his turn. I watched him being sheared from the warm shower. When she was done with him, it was my turn again. She opened a big can of black ointment, dipped her hand in, and began smearing the stuff on me from my bald head all the way down to my toes. It had a sickening foul smell. „Wait here,“ she said when she was done.

She went on to smear the black ointment on Peter with great care, making sure there were no bald spots. I was mesmerized by the scene, could not take my eyes off them. When she was finished with him, he looked like a burnt corpse standing up. „I will put these in the fire,“ she said, gathering our clothes. „I will be back in a minute with proper clothes!“ She was out the door.

Finally, we were ready, presentable. There was a small mirror hanging over the sink. I was looking at it, trying to make up my mind. Do I want to see what I looked like before being presented or not? It was a shock seeing myself: I was gone. The only thing left of me were my eyes and lips. I looked like Peter.

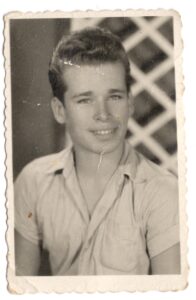

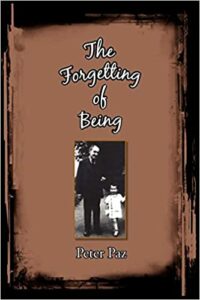

Peter Paz, The Forgetting of Being (4)

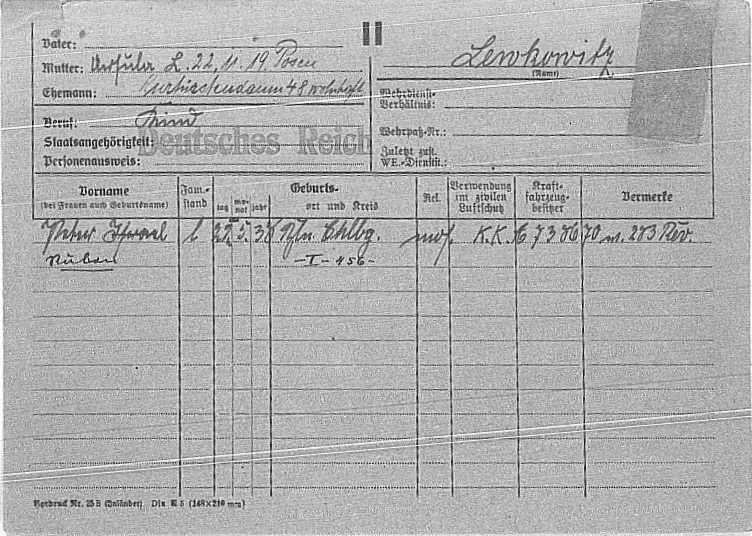

[*Peter Paz dated this one year early / Peter Paz datierte die Ankunft in Haifa ein Jahr zu früh]